Reeds Memoriam

By Jennie K. Williams, Ph.D.

On December 31, 1827, three men—Robert Beverly Corbin, Edward Rawle, and Francis Porteus Corbin—secured ownership of a sugar plantation on the western bank of the Mississippi River in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana. The land itself was not new. Surveyed in 1793 under Spanish colonial rule, it had already passed through multiple regimes and owners. What was new was the human world these men would forcibly assemble upon it. Over the next several years, they would traffic, purchase, and concentrate 129 enslaved people from Virginia, Maryland, and Mobile, Alabama, binding together families, strangers, and survivors of earlier migrations into a single, fragile community. Nearly half would die there. All who survived would be sold.

This story is not only one of brutal labor and staggering mortality. It is also a story about the limits of an assumption long embedded in histories of slavery: that planter-led migrations were somehow less destructive to enslaved families than sales carried out by professional traders. At the Corbin-Rawle plantation, kin were indeed moved together. But what followed—the grinding labor of sugar, epidemic disease, debt, and eventual liquidation—reveals how planter migration could fracture families repeatedly and belatedly, long after the initial journey south.

Left: Detail of Mitchell & Young, "Map of Virginia and Maryland, constructed from the latest authorities" (1838). Right: Detail of La Tourrette's Map of Louisiana (1848). Both maps are from the Library of Congress.

Assembling a Plantation People

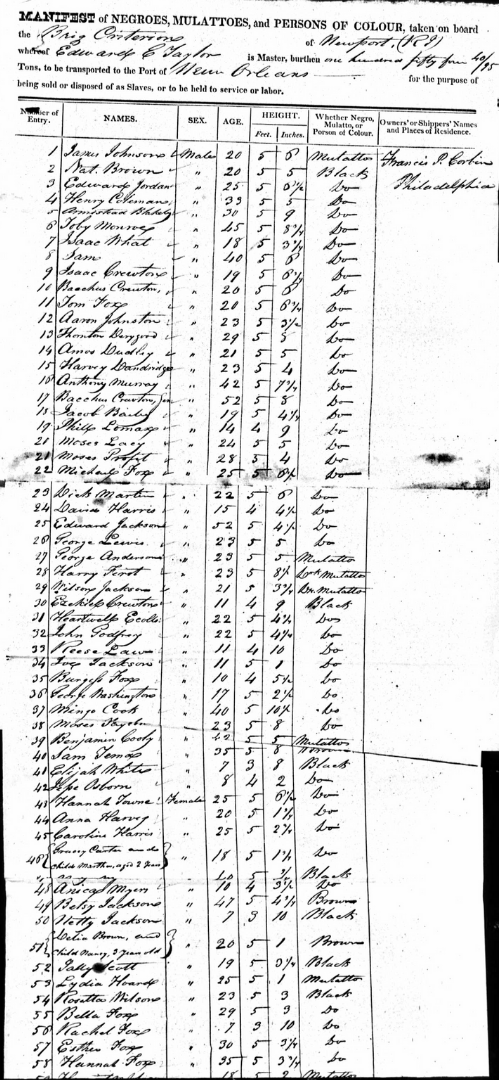

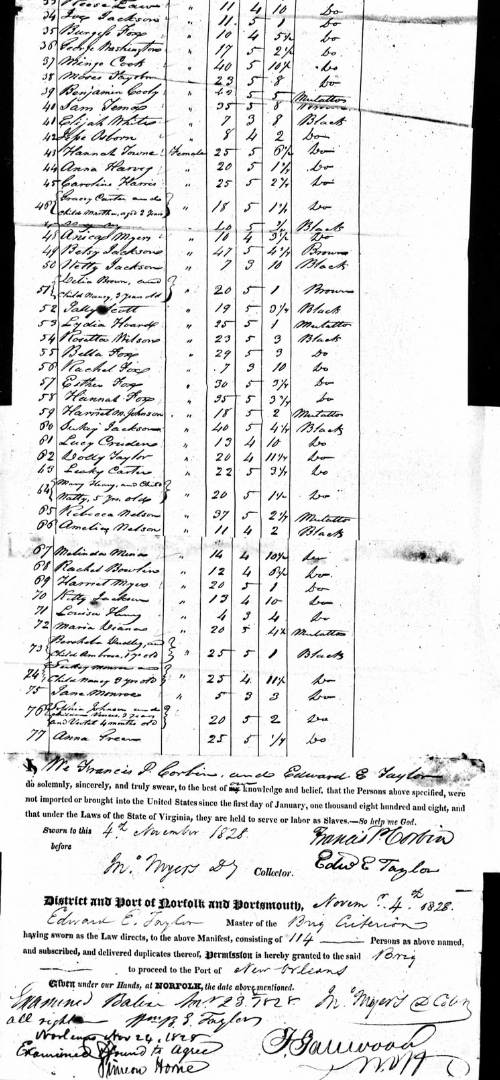

Between February 1828 and April 1830, Corbin, Corbin & Rawle assembled the labor force for their Louisiana venture in four major acquisitions of enslaved persons. The first group arrived in February 1828: sixteen people trafficked from Mobile to New Orleans aboard the steamboat St. John. They included five adult men, eight adult women, and three children, one of them an infant just two months old. Although the ship’s manifest listed Edward Rawle as their owner, their earlier lives are obscure. They may have been connected to Rawle’s father-in-law, Joseph Saul, a trader whose business networks ran through Mobile and West Florida. What is certain is that they arrived already bearing relationships—mothers and children, men and women who would later form marriages, and people whose lives had already been shaped by sale and movement.

Manifest of the steamboat St. John’s voyage from Mobile, AL to New Orleans, LA (1828). Image: National Archives via the Oceans of Kinfolk Database.

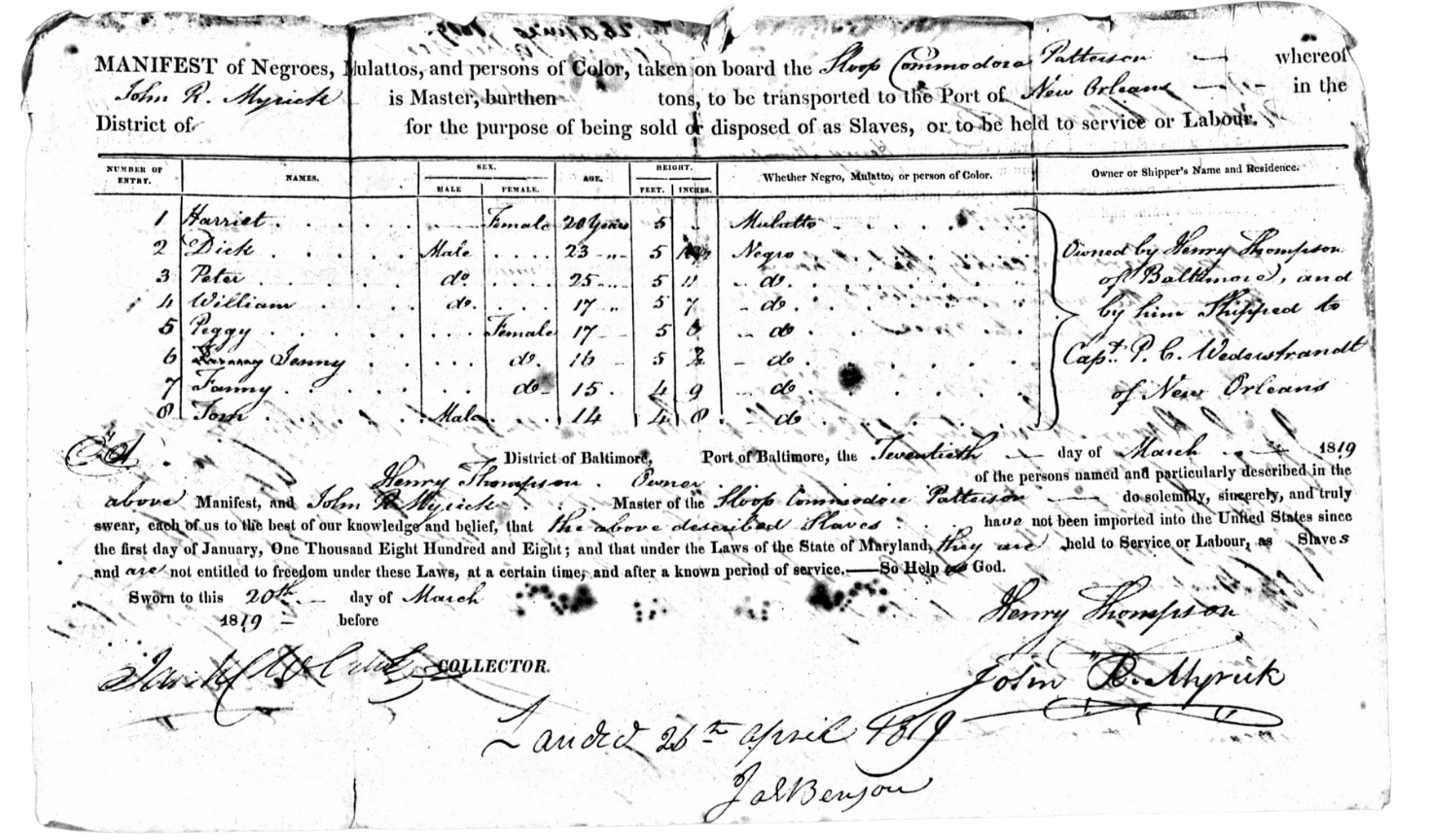

Later that same month, Corbin, Corbin and Rawle purchased twelve more enslaved people—nine adult and three children—from William Riggin of Baltimore. Unlike the Mobile group, the nine adults had been enslaved in Louisiana for nearly a decade, having been trafficked from Maryland to Louisiana in 1819 by Maryland native Henry Thompson, part-owner of a sugar plantation, “Magnolia Grove,” in St. Bernard Parish. While enslaved at Magnolia Grove, the nine adults had formed new roots: children were born, households re-formed, and experience with sugar cultivation was gained. Their sale in 1828—likely anticipated and feared—represented a second uprooting. In fact, at least one man, Tom, fled Magnolia Grove when rumors of the impending sale spread, underscoring how deeply enslaved people understood the stakes of planter insolvency.

Left: Manifest of the sloop Commodore Patterson’s voyage from Baltimore, MD to New Orleans, LA (1819). Right: New Orleans Argues, January_19_1828 Magnolia Grove Tom

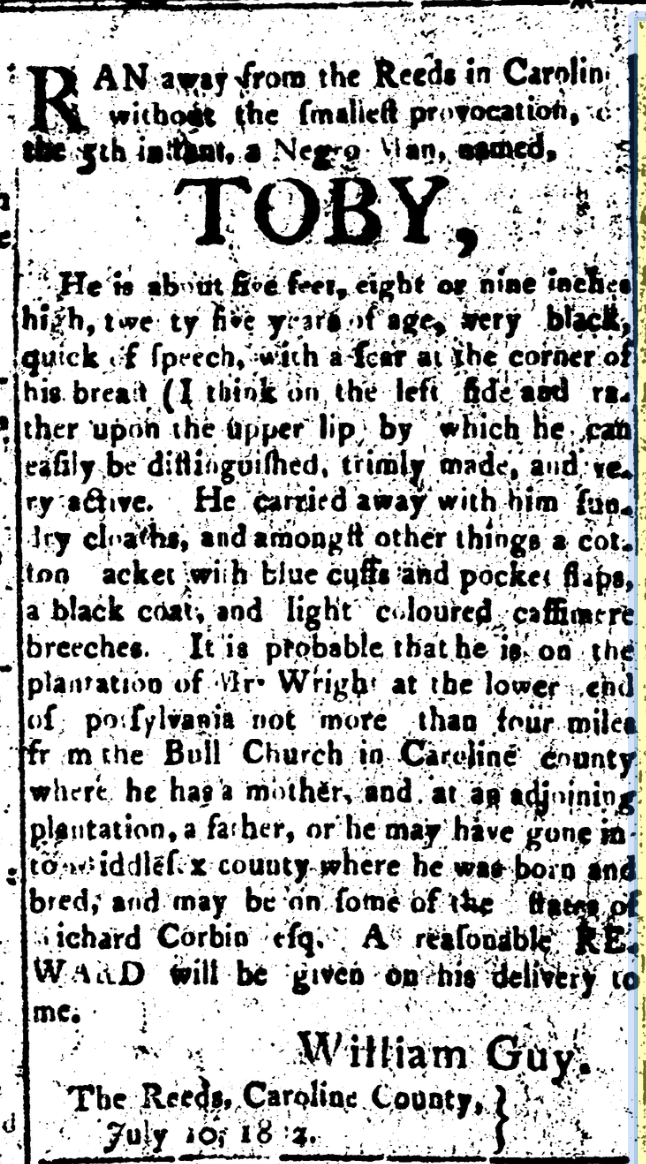

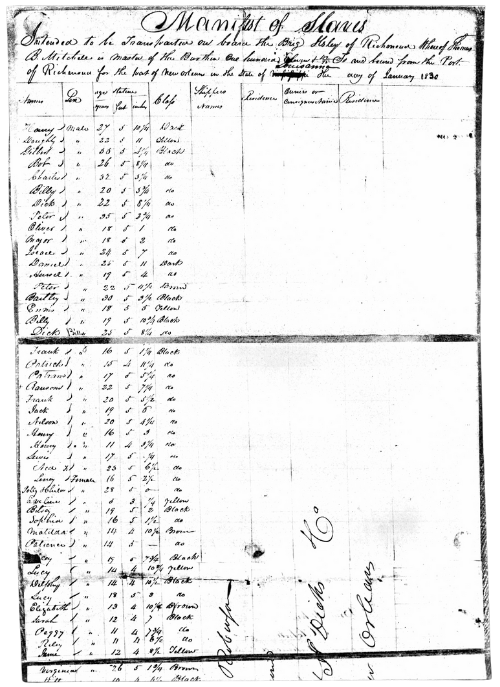

The largest group arrived in November 1828: eighty-two men, women, and children shipped from Virginia aboard the brig Criterion. Most had been enslaved for generations on Corbin family plantations in Caroline County, especially the Reeds estate. Their forced removal marked the culmination of a long lineage of enslavement under the same family name. For people like Toby Monroe—who had once fled the Reeds in 1802, only to be recaptured and eventually carried south—this migration represented not a rupture from a single place, but the extension of captivity across generations and geographies.

Left: Virginia Herald, July 20, 1802. Middle and right: Manifest of the brig Criterion’s voyage from Norfolk, VA to New Orleans (November 1828).

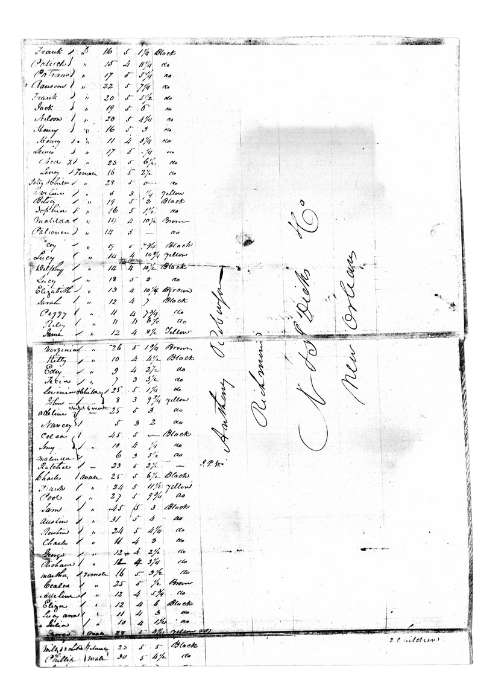

Corbin, Corbin and Rawle purchased a final group of nineteen enslaved people in New Orleans in April 1830 from trader Abner Robinson, most of them recently trafficked from Richmond or Norfolk. With this acquisition, the Corbin-Rawle plantation reached its full enslaved population: 129 people, the majority between the ages of fifteen and twenty-nine, and predominantly from the Chesapeake.

Excerpts of manifest of the Ilsley’s voyage from Richmond, VA to New Orleans, LA (1830).

Louisiana Sugar: A World of Risk

Jefferson Parish in the late 1820s was newly created but already deeply shaped by slavery. Enslaved people made up more than three-quarters of its population, most living on large plantations. The Corbin-Rawle place sat among some of the region’s largest sugar estates, in a landscape where French and English mingled, and where newcomers from Virginia and Maryland quickly learned that Louisiana was deadly in ways they had never known.

Sugar cultivation demanded unrelenting labor. From planting to harvest to processing, the work required speed, strength, and precision. Enslaved people dug massive holes or trenches, weeded constantly, cut cane with razor-sharp knives, and fed stalks into steam-powered rollers that could maim or kill in an instant. During the grinding season, workdays stretched to eighteen hours. Contemporary observers—planters, travelers, formerly enslaved people—agreed on one point: sugar production consumed lives.

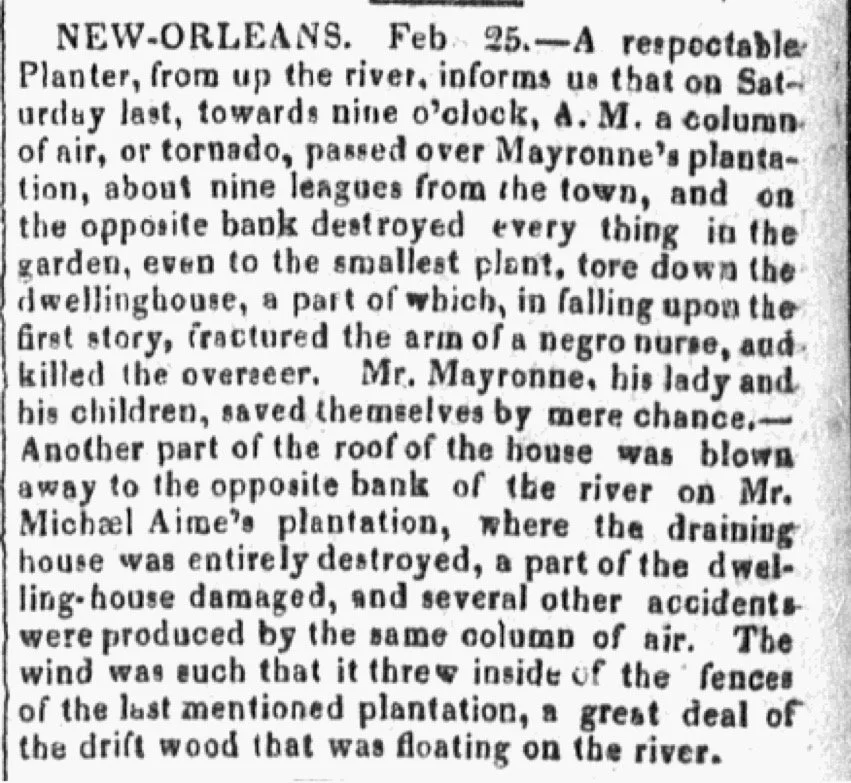

The climate compounded these dangers. Floods, droughts, frost, and hurricanes threatened crops and livelihoods, placing constant pressure on planters to extract as much labor as possible when conditions allowed. Disease was even more devastating. Yellow fever, malaria, and measles circulated regularly, but cholera proved catastrophic. Enslaved people newly arrived from the Chesapeake had little immunity, and epidemics swept through plantations with terrifying speed.

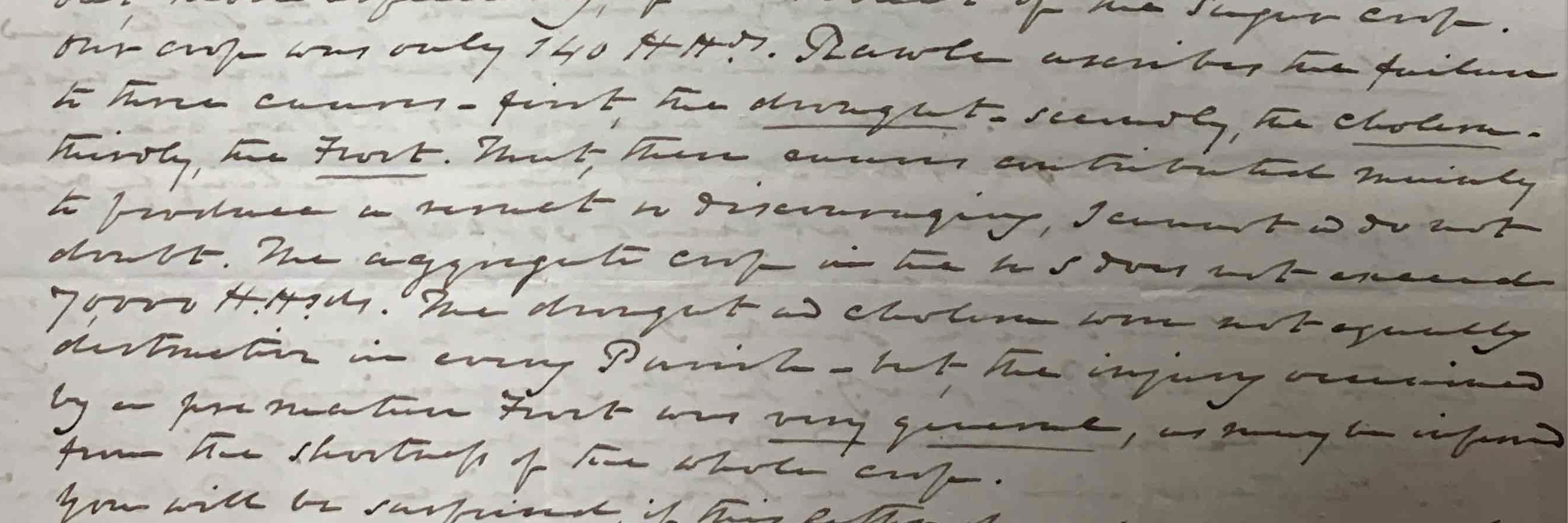

Left: Farmer’s Cabinet, March 29, 1828. Right: Excerpt of letter from Robert Beverley Corbin to Edward Rawle regarding their plantation, April 5, 1834. The excerpt reads: “Our crop was only 140 HH [hogsheads]. Rawle ascribes the failure to three causes – first, the draught. Secondly, the cholera. Thirdly, the frost. That these causes contributed mainly to produce a result so discouraging I cannot and do not doubt. The aggregate crop is in the [illegible] does not exceed 70,000 HH [hogsheads]. The draught and cholera were not equally destructive in every Parish, but the injury sustained by a premature frost was very general…”.

Life, Labor, and Loss

On the Corbin-Rawle plantation, white oversight was minimal. Edward Rawle was the only owner consistently present, while his partners lived in Virginia, Philadelphia, or abroad. Much of the plantation’s daily order rested on enslaved drivers—men like Dick and David from the Riggin group—who had survived nearly a decade of sugar labor before their arrival and were tasked with enforcing discipline among others.

Work was assigned relentlessly. Children labored in the house and fields; elderly and injured people were reassigned rather than spared. Every person worked, at every stage of life. By 1833, despite births among the enslaved population, death had already taken a devastating toll.

Of the 129 people brought to the plantation, only 92 remained. There is no evidence of sale during those years. The most likely explanation is death.

The cholera epidemics of 1832 and 1833 accelerated this devastation. Enslaved people died within hours of showing symptoms. Entire families were struck. In desperation, Rawle ordered the population to abandon their quarters and camp in the woods, disrupting labor but failing to halt the disease. Visitors from neighboring plantations—friends, kin, loved ones—carried the infection with them, illustrating how enslaved people’s networks of connection, so vital for survival, also made them vulnerable in moments of crisis.

Children continued to be born, but survival was precarious. Of twenty-nine infants born between 1828 and 1837, roughly half died before reaching their second birthday. Naming patterns reveal layers of grief and memory: children named for the dead, marriages re-formed after loss, families stitched together again and again under impossible conditions.

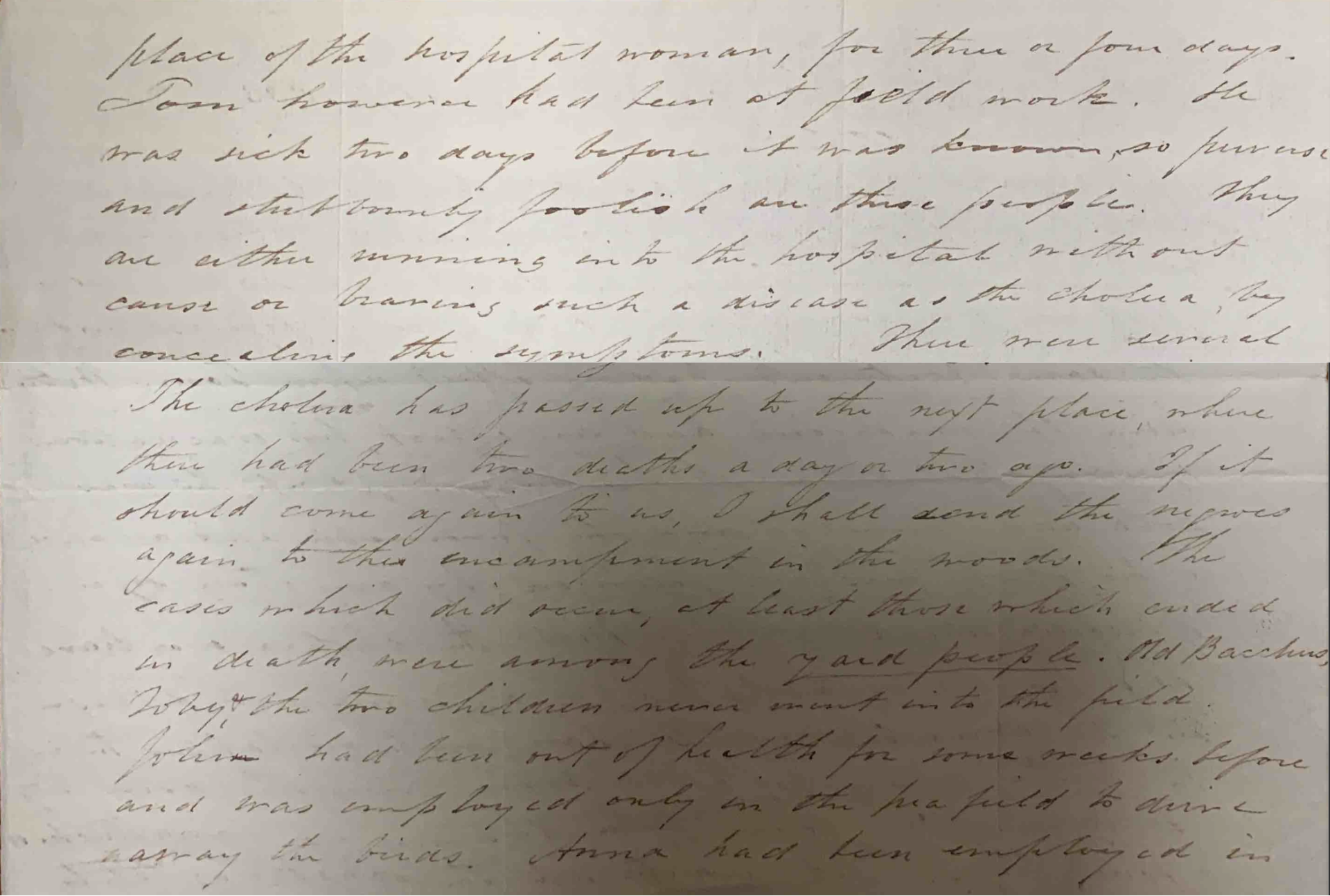

Excerpt of letter from Robert Beverley Corbin to Edward Rawle, August 7, 1833. The excerpt reads: “The cholera has passed up to the next place where there had been two deaths a day or two ago. If it should come again to us, I shall send the negroes again to the encampment in the woods. The cases which did occur, at least those which ended in death, were among the yard people. Old Bacchus, Toby and the two children never went into the field. John had been out of health for some weeks before and was employed only in the pea field to driveway the birds. Anna had been employed in the place of the hospital woman, for three or four days. Tom however had been at field work. He was sick two day before it was known, so perverse and stubbornly foolish are these people. They are either running into the hospital without cause or having such a disease as the cholera by concealing the symptoms.”

Debt and Disintegration

Behind the scenes, the plantation was failing financially. Corbin, Corbin & Rawle mortgaged their land and enslaved people repeatedly, borrowing heavily from banks and merchants. Bad harvests, disease, and their own inexperience left them unable to repay their debts. By the mid-1830s, creditors made clear what enslaved people already knew: liquidation was inevitable.

For enslaved families, planter failure was as dangerous as planter ambition. When crops failed, enslaved people themselves became the currency used to settle accounts. And so it was for the individuals and families enslaved by the Corbin brothers and Edward Rawle in Louisiana.

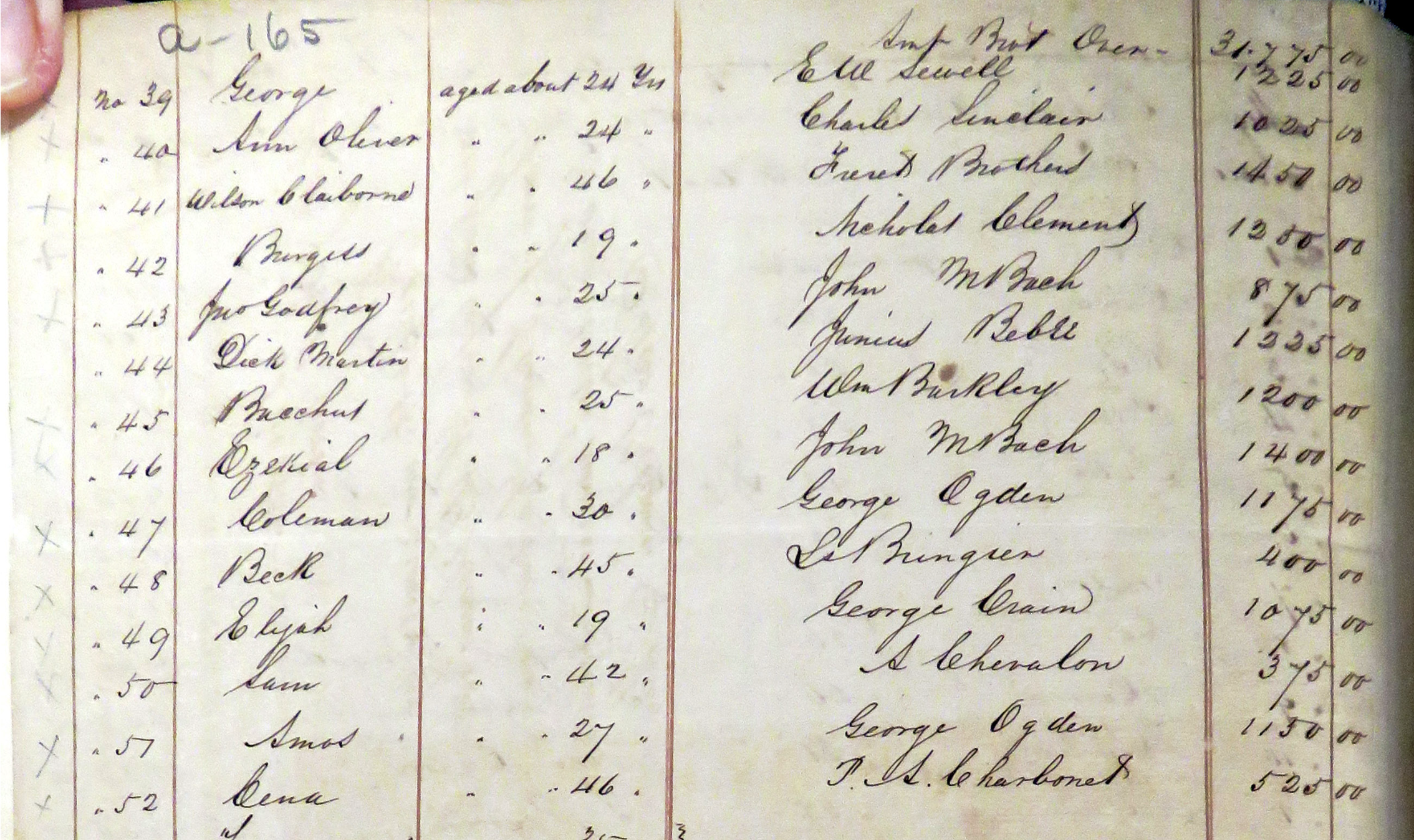

In April 1837, the owners sold more than one hundred people at auction in New Orleans. Husbands and wives, parents and children, siblings who had survived years of forced labor and disease together were separated in a single afternoon.

Families like the Crewtons, the Foxes, and the Dudleys—each of whom had arrived together from Virginia—were scattered among multiple buyers. Infants were sold with or without their mothers. Young adults were valued for strength and skill; older people were sold cheaply or disappeared from the record entirely. The auction took place at Hewlett’s Exchange, a refined urban space, amid chandeliers and paintings. Descendants of the individuals trafficked to Jefferson Parish by the Corbin brothers and Edward Rawle remain in Louisiana to this day.

Excerpt of notarial record listing enslaved persons sold by Corbin, Corbin and Rawle via auction on April 29, 1838 as cited in the Louisiana Kindred database.

Rethinking Planter Migrations

The experience of the Corbin-Rawle people complicates easy distinctions between planter migration and the domestic slave trade. It is true that many arrived in Louisiana with kin and were not immediately sold upon arrival. But this temporary continuity masked a deeper instability. Over nearly a decade, planter debt, environmental disaster, disease, and managerial failure subjected enslaved families to repeated trauma. When the end came, it was total.

For those enslaved on the Corbin-Rawle plantation, forced migration did not end with arrival in Louisiana. It continued through illness, reassignment, remarriage, burial, and ultimately sale. Kinship was not simply destroyed once; it was tested, re-formed, and shattered again.

Their story reminds us that slavery’s violence was not confined to moments of sale or transport. It unfolded over years, through labor regimes that consumed bodies, economic systems that treated people as collateral, and migrations that promised continuity but delivered devastation. In tracing these lives—across Virginia clay, coastal waters, and Louisiana mud—we see not only loss, but endurance, memory, and the fragile persistence of kinfolk against impossible odds.